Why Tesla Won't Grant Musk More Stock Options

Musk is campaigning for more stock grants. And in the wake of the Tornetta decision, his biggest fans are demanding that the Tesla board restore what was lost. Here's why I don't believe it can happen

[Apologies for having taken so long to post again on Substack. Here’s hoping my future posts are more frequent and shorter!]

Post-publication note on May 10,2024:

It didn’t take long for Tesla to prove me wrong in my assertion that it would not grant Musk more stock options, as on April 17 it filed a proxy statement that, among other things, asks Tesla shareholders to “ratify” the 2018 compensation package. Well, not completely wrong. There is no new grant. Instead, Tesla is attempting to have shareholders breathe life into the 2018 grant that was voided by Chancellor McCormick.

When I wrote this post, I had not considered the possibility of ratification under Section 204 of the Delaware General Corporation Law because, to my way of thinking, that is a vehicle for curing problems with the requisites of statutory authorization rather than a means of curing a breach of fiduciary duty.

Will that maneuver work? To be determined.

I was also wrong about the independence of Kathleen Wilson-Thomson, as I neglected to do my homework. Her independence is crucial because, in the ratification effort, she acted as a “committee of one” based on her supposed independence. Had I done a bit more research, I would have learned that she has already received $62 million in pre-tax proceeds from the sale of Tesla stock that she acquired as compensation for serving as a Tesla director; that she still owns another 771,255 shares; and that she has sold, or is in the process of selling, 280,000 of those shares pursuant to a so-called Rule 10b5-1 trading arrangement. I’ve written more about that in a subsequent post. Adding it all up, Wilson-Thompson has been enriched by close to $200 million for her five years of service as a Tesla director.

Under Delaware law, market-rate compensation does not compromise a director’s independence, but outsized compensation can. Footnote 644 on page 126 of the Tornetta decision points to this case law. I would expect any legal challenge to Tesla’s ratification effort to include a challenge to Wilson-Thompson’s independence.

As most readers here know, earlier this year Elon Musk lost an immensely consequential case in Delaware’s Court of Chancery. On January 30, the Chancellor, Kathaleen St. Jude McCormick, published a 200-page opinion rescinding an equity compensation plan that Tesla Inc.’s Board of Directors had awarded Musk six years ago. The opinion in the case, Tornetta v. Musk, is written with admirable clarity and organization, and is well worth a read.

Days before Tornetta was handed down, Musk began campaigning for a massive Tesla stock grant (essentially, to restore to him the Tesla stock he sold to buy Twitter). And, since Tornetta, many Musk fans have urged that the Tesla board undertake a “do-over” and, by cleaning up the mistakes made in the 2018 process, restore to Musk the munificent stock option grant that the Chancellor rescinded (an example is here).

In this post, I explain why, for three separate reasons, any new compensation package featuring stock options (at whatever price) is unlikely to happen.

First, were Tesla board members to attempt any retroactive restoration of Musk’s 2018 compensation package, or anything resembling it, they would expose themselves to lawsuits for breach of fiduciary duty and corporate waste.

Second, the business environment in which Tesla finds itself in 2024 is radically different from that which Tesla enjoyed in 2018. Capable – and often superior – competition has arrived in force, while at the same time the public’s appetite for electric vehicles appears to have been largely sated, even in the face of the governmental stimulants of subsidies and mandates.

·Third, and most importantly, given the “market cap” and EBITDA incentives dangled by 2018 compensation package, Musk quite predictably employed tactics calculated to achieve short-term share price appreciation, including making fantastic predictions about imminent Tesla breakthroughs (most particularly, “robotaxis”) while putting capital spending on a diet to enhance the cosmetics of the financial statements. Consequently, the dramatic spike in Tesla’s share price was unsustainable. The promised breakthroughs failed to materialize, the starvation of capital expenditures resulted in a stale product line, and Musk’s business model for Tesla proved to be fragile. Thus, at today’s much-diminished and still-falling market cap, Musk’s 2018 package has already proved to be an embarrassing mistake.

I. The Tornetta Decision

When Richard J. Tornetta (a former heavy metal drummer with a band called Dawn of Correction) filed his complaint in June of 2018, he faced daunting odds. Far and few are the compensation plans ever upended by the courts, especially the Delaware courts. Over the years, Delaware has fashioned a rule that is exceptionally broad in the latitude it grants to a corporation’s board of directors when making decisions involving business judgments, including decisions about compensating the company’s officers. As the Tornetta opinion acknowledges:

A board of director’s decision on how much to pay a company’s chief executive officer is the quintessential business determination subject to great judicial deference.

So, how did Musk manage to have his compensation plan evaluated under the restrictive “entire fairness” standard rather than the lax business judgment rule, and then see the plan fail the entire fairness test? These failures required a perfect storm of bad facts. First, Musk himself devised the plan, dictated the timetable for the board’s deliberations, and essentially negotiated against himself while Tesla’s board all but made clear they were eager to cooperate so that he could do as he wished. In the Court’s words, Musk “dominated the process that led to board approval.”

Second, various board members, despite having close personal and financial ties to Musk, described themselves as “independent” in the proxy materials that the shareholders were asked to consider before voting. (The proxy materials were also misleading in other ways, including omitting Musk’s enormous role in formulating the plan, but the Chancellor’s legal analysis did not rely on that deficiency because other considerations were sufficient for her analysis.)

At the bottom of it all was the size of the package. The stock option plan, as the Chancellor detailed,

is the largest potential compensation opportunity ever observed in public markets by multiple orders of magnitude—250 times larger than the contemporaneous median peer compensation plan and over 33 times larger than the plan’s closest comparison, which was Musk’s prior compensation plan.

The potential value of Musk’s stock options was more than $55 billion. That is more than a magnitude greater than the total net profit Tesla has earned in its entire 13-year history as a public company.

Even worse, as the Chancellor noted, the Tesla board never asked this essential question: was the compensation plan necessary to incentivize Musk? In 2018, he already owned 21% of Tesla, meaning that every $50 billion in increased market cap would increase his net worth by $10 billion.

Citing a law journal article, the Chancellor labeled Musk as the paradigmatic “Superstar CEO.” The problem with such Superstar CEOs is the tendency of directors to defer to them, essentially rubber-stamping the executive’s decisions that, in a properly governed company, would be made by the board.

A. The Bad Facts Become Even Worse: Cocaine, Ecstasy, Etc.

At Tesla, the deference problem ran even deeper than the many ways detailed by the Chancellor. Six days after the Tornetta decision was handed down, The Wall Street Journal published a blockbuster article entitled The Money and Drugs That Tie Elon Musk to Some Tesla Directors. It explored not simply the extensive financial and personal ties between Musk and Tesla directors that Chancellor McCormick had noted, but also the way in which some directors had become complicit in Musk’s illegal drug use:

In the culture Musk has created around him, some friends, including directors, feel there is an expectation to consume drugs with him because they think refraining could upset the billionaire, who has made them a lot of money, some of the people said. More so, they don’t want to risk losing the social capital that comes from being close to Musk, which for some feels akin to having proximity to a king.

It is difficult to imagine that the Wall Street Journal reporting won’t greatly complicate any Musk appeal of Tornetta to the Delaware Supreme Court. Indeed, that reporting adds emphatic support to the fact findings of the Chancellor’s opinion.

B. Musk Threatens Tesla’s Board & Shareholders

While Musk has complained bitterly about the Tornetta decision, and almost surely will initiate an appeal once there is a final ruling (as I write this, the issue of attorneys’ fees has yet to be resolved), I believe he and his lawyers will realize they have little chance of reversing the decision. Consequently, even while pursuing his appeal, Musk likely will urge the Tesla board to formulate an equity incentive plan to replace the one invalidated by Delaware’s Court of Chancery.

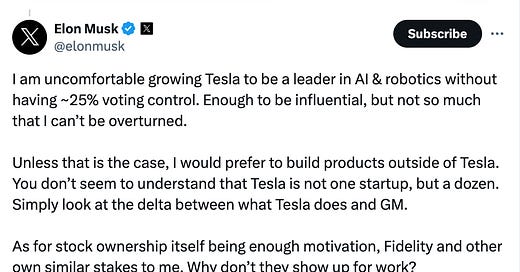

Indeed, a few days before the Tornetta decision, Musk himself began a campaign to be awarded more stock ownership:

Audacity, thy name is Elon Musk. As Drew Dickson wrote in the Financial Times:

Yes, you read that correctly. Elon effectively said that if he isn’t given a new pay package that grants him more shares of Tesla, he would consider building any AI and robotics products outside of the Tesla umbrella (sort of like SpaceX does with rockets).

In Delaware (and, so far as I know, in every other U.S. state), the “corporate opportunity doctrine” prohibits a corporate fiduciary from appropriating –from a public company to another entity in which he or she has an interest – any business opportunity already being developed or exploited by the public company. So, in essence, Musk is openly threatening to breach his fiduciary duty to Tesla. And, indeed, he has already followed up on that, both by starting his own artificial intelligence company, xAI, and then by having xAI poach Tesla’s AI engineers.

As always, the temptation to go too far afield arises with any essay about Elon Musk. So, I’ll resist it here and simply say that in the unlikely event that xAI ever becomes profitable, the breach of fiduciary duty lawsuits from Tesla shareholders will be things of beauty to behold.

The relevant point for present purposes is that in making his threat, Musk seeks restoration of the Tesla ownership share he enjoyed before he made history’s worst business decision by single individual: the Twitter acquisition. Before the Twitter acquisition fiasco, Musk owned 22% of Tesla. When he sold Tesla stock to finance the Twitter purchase, that shrunk to about 10%. From the Financial Times article:

So, if Elon insists on getting back up to the 25 per cent control (which he now wants), Tesla will either have to create a dual-share structure (which Elon now says he is “all for”, having publicly disparaged others for taking the same path) or issue him over 137mn shares (or options to buy those shares). And this 137mn share gift would be amazingly similar to the 141 million shares Elon sold for $275 a share!

Even if the Board is inclined to (once again) bend to Musk’s wishes, I doubt that it can. As I explain below, devising a substitute compensation plan will be far more difficult than simply awarding Musk the amount of stock he would have received under the 2018 plan, even if the award process is purged of the disclosure defects.

II. Tesla’s Governance Is Deeply Defective

What was needed for the 2018 compensation plan to have passed judgment under Delaware law? I’m going to assume that no Delaware court will disturb the Chancellor’s determination that Musk was and remains a “controlling shareholder” of Tesla, notwithstanding that his ownership share is well below 50%. The evidence marshalled by the Chancery Court is simply overwhelming on that point.

Consequently, for the 2018 plan to have been properly approved, it would have required both a vote by (1) a special committee of truly independent directors and (2) disinterested shareholders casting their votes with the benefit of a materially accurate proxy statement. (As a note, the shareholder vote on the 2018 plan was necessary only because the Tesla board made it a condition. However, in light of the subsequent Delaware Supreme Court decision in In re Match Group, Inc. Derivative Litigation, the vote of both an independent special committee and fully informed disinterested shareholders is now required to escape an “entire fairness” review.)

So, now let us consider whether any independent special committee of Tesla directors is likely to try to restore some or all of the wealth that Musk lost in Tornetta. Let’s start by asking, who are the potential members of such a committee? In other words, which directors are actually independent?

Tesla’s eight-person board today includes five members whom the Chancellor already determined are not independent: Elon Musk, brother Kimbal, Ira Ehrenpreis, James Murdoch, and Robyn Denholm. (Musk argued that Denholm was independent in 2018; the Chancellor disagreed. However close that call might have been for 2018, it’s no longer close, as Denholm has since then received well north of $300 million from sales of Tesla stock that came to her via stock options as part of her director compensation.)

A sixth director – J.B. Straubel – derived most of his wealth (estimated at $1.3 billion) from Tesla during his 15-year tenure as Tesla’s Chief Technical Officer and has a long and close personal relationship with Elon Musk. I think it’s safe to assume that Straubel, too, falls into the conflicted director basket.

That leaves only two truly independent directors: Kathleen Wilson-Thompson (appointed in late December of 2018) and Joe Gebbia (appointed in September of 2022).

[I was wrong about Wilson-Thompson. See the post-publication note at the top of this post.]

III. Tesla’s Declining Business Precludes More Stock for Musk

What are the chances that these two directors, even if joined by other independent directors in the future, would attempt to restore to Elon Musk the stock options he lost, or any stock or stock options at all, by way of another compensation package?

A. Tornetta Posed a Question That Has No Good Answer

Any special committee of independent directors would have to consider why Musk lost the Tornetta case, and what it would take to prevail in any Round 2. In particular, they would have to consider this passage from Tornetta:

At a high level, the “6% for $600 billion” argument has a lot of appeal. But that appeal quickly fades when one remembers that Musk owned 21.9% of Tesla when the board approved his compensation plan. This ownership stake gave him every incentive to push Tesla to levels of transformative growth—Musk stood to gain over $10 billion for every $50 billion in market capitalization increase. Musk had no intention of leaving Tesla, and he made that clear at the outset of the process and throughout this litigation. Moreover, the compensation plan was not conditioned on Musk devoting any set amount of time to Tesla because the board never proposed such a term. Swept up by the rhetoric of “all upside,” or perhaps starry eyed by Musk’s superstar appeal, the board never asked the $55.8 billion question: Was the plan even necessary for Tesla to retain Musk and achieve its goals?

Therein lies the principal problem: Musk has already benefitted munificently from the ascent of Tesla’s market capitalization simply by reason of the 21.9% of Tesla that he owned before the 2018 plan came into being. Indeed, in 2022 alone, he sold $23 billion worth of Tesla stock.

How would a grant today of more stock options benefit Tesla? The stratospheric rise in market capitalization and revenues that the board hoped for in 2018 materialized several years ago. It is easy to imagine that any attempt to restore, even partially, what Musk lost in Tornetta would quickly give rise to powerful claims of breach of fiduciary duty or corporate waste. How likely is it that truly independent directors would want to sign on to that kind of potential liability?

B. Musk Needs the Liquid Wealth Tesla Gives Him

As we’ve seen, Musk is threatening to leave Tesla altogether. Would a plan designed to keep him in place be supportable on that basis? This kind of brazen blackmail is, to say the least, unusual in corporate America. But is the blackmail even credible? As Matt Levine has pointed out, Musk has lots of reasons to stay:

Even now, Musk has good reasons for doing his next good idea at Tesla. It’s the biggest of his companies, so it has a lot of capacity to do things. It’s the largest portion of his fortune, so increasing its value does the most for his wealth. It’s the most liquid portion of his fortune — he can sell or borrow against Tesla shares much more easily than the rest of his companies — so increasing its value does the most for his practical buying power. It’s the company with which he is, still, probably, most associated in the public imagination, so doing stuff at Tesla probably does the most for his reputation.

C. Musk’s Awards Are Melting Away

Besides the reasons offered by Levine, there’s another reason that any attempt to restore to Musk what he lost in Tornetta would be highly problematic. The 2018 compensation package awarded Musk stock options based on (1) eight market capitalization milestones that needed to be paired with (2) eight operational milestones, which could be either increases in revenue or in adjusted EBITDA (besides subtracting interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization from earnings, the adjustment also subtracted stock-based compensation). By the end of June of 2022, all eight of the tranches vested. However, since then, the increases in market capitalization have begun to melt away, and both Tesla’s revenues and its adjusted EBITDA have declined precipitously, with more declines likely in 2024.

Tesla saw its all-time high share price of $409.97 on Nov. 4, 2021, which translated to a market capitalization of about $1.2 trillion, or almost double the $650 million market cap that Musk needed to satisfy all eight market cap milestones. However, from that all-time high, the market cap has collapsed (as I prepare to publish this after the market close on April 8, 2024) to only $551 billion, which is below the amount for which the eighth tranche of the options was awarded, and perilously close to the amount ($550 billion) for which seventh tranche was awarded.

D. Tesla’s Prospects Have Dimmed Considerably

The collapse in the market capitalization is no accident. For years, Tesla was the only electric vehicle (EV) game in town. It benefitted not only from generous subsidies and tax breaks that reduced its costs and padded its revenues, but also from policies that punished its competitors, forcing them to pay Tesla every time they sold an internal combustion vehicle.

As always happens, however, subsidies attract competition like slops attract pigs. Every large automaker, and many smaller ones, began planning their own EVs. Now, Tesla is sailing into a competitive storm. With scores of EVs to choose from (and more announced every month), the professional reviewers (and consumers) increasingly judge many of the competitors’ offerings to be better than those of Tesla.

Now, the market is flooded with EVs. The early adopters, the true believers, the tax write-off seekers, and the greenwashers have sated their appetites. Regular consumers, pushed into EVs by the subsidies and mandates, are troubled by the downsides: long recharging times, limited range, and – possibly worst of all –the inevitable capacity degradation the batteries suffer, resulting in the need for costly replacement ($20k+) after several years of use. Despite the determined efforts of Western governments to coerce their citizens into driving EVs, the dogs simply won’t eat the dog food.

Faced with a sudden tsunami of competition and having saddled itself with costly overcapacity by the recent addition of factories in Germany and Texas, Tesla badly needs to maintain volume. Indeed, with a stratospheric share price premised on massive growth for years to come, Tesla needs to be materially increasing volume. Consequently, it has been forced to cut prices. Price-cutting, though, comes with a price: dramatically reduced margins.

As Q1’s shocking drop in deliveries underscores, even the price-cutting has not been sufficient to maintain volume. As prices, margins, and deliveries continue to shrink, analysts are constantly slashing future earnings estimates. The “robotaxi” and Full Self-Driving narratives are no longer believable. Dojo and Optimus are sad jokes. The Cybertruck, which finally arrived with a much lower range and higher cost than promised, will almost surely be a niche product that, at best, breaks even. The Models S, X, 3, and Y are long in the tooth, and the promised $25k “Model 2” is nowhere to be seen. (Regarding the Reuters article reporting that the Model 2 has been scrapped, Musk’s immediate accusation that Reuters is lying, and Musk’s subsequent tweet that Tesla will “unveil” its robotaxi on August 8, Brad Munchen and Anton Wahlman have the definitive analyses.)

E. A Further Decline in Share Price Seems Inevitable

As I write this, Tesla sports a price-to earnings (P/E) ratio of somewhere between 45 and 85, depending on one’s estimate of 2024 earnings. In other words, a magnitude higher than the P/E ratios seen in the rest of the automotive industry. The Tesla bull story is that Tesla is a technology company whose future growth will come from artificial intelligence or its Full Self-Driving software. Yet the reality is that about 94% of Tesla’s revenues comes from selling cars, and the remaining 6% comes from its (even lower margin) solar energy and battery storage products.

There are many reasons to believe that Tesla’s share price will continue under pressure until its financial metrics come to resemble those of other automakers. That translates to a share price of somewhere between $15 and $30. And that assumes that generous EV subsidies, along with mandates and regulations that punish the production of internal combustion vehicles, will continue in effect.

Consequently, it is doubtful that Tesla will ever again achieve the $650 billion market cap that allowed Musk to earn all of the eight tranches under the 2018 plan. Far more likely is that the market cap will continue shrinking until even the first of those tranches would be a stretch.

So, we are likely to see an increasingly unhappy Elon Musk, trapped at Tesla, doing all he can to keep the boat afloat with stock pumps, but facing a losing battle as the bad business news continues to pile up. When and where it all ends is impossible to say, but the odds are that it won’t end well.

As always, a spectacular effort Mr Fossi! Separately, I just turned down an opportunity to invest, pre-IPO, in xAI as I too have concerns about how Musk is holding Tesla shareholders and the Board hostage. So we are left to wonder if/when the loyal shareholders of TSLA ever become frustrated with the perceived(or actual) damage Musk has inflicted upon what has become a success story* at Tesla. This behavior remains foreign to me after a few decades of working for Boards that take their governance responsibility seriously.

*I've learned we don't have to agree with how those loyal to Tesla view success but sometimes I find myself marveling at what he has built against big hurdles. And then Musk again delivers the behavior that defies common decency.

Thanks for writing this!

Quick question:

III A. "Was the plan even necessary for Tesla to retain Musk and achieve its goals?"

Does this matter? Is the company bound to an upper limit of what is "necessary to retain" to CEO? Can they pay more?